“Thank God they’re so stupid. If they were smart, if they regarded murder as a secret and heinous act, if they told no one, if they got rid of the clothing and the weapon and the possessions taken from the victim, if they refused to listen to bullshit in the interrogation rooms, what the hell would a detective do?”

Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets

David Simon

If you read the About page on this site, particularly the individual content sections explaining THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD’s video, audio, and literary proclivities, you already know the author consumes a lot of true-crime content. Today, for example, THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD is watching back episodes of Snapped on the Oxygen True Crime app on his smart TV — in particular, “Nancy Khan” (S26, E3) which premiered, Sunday, September 15, 2019. This episode details “an investigation into the murder of a successful business manager and expecting father [which] leads Texas detectives to a seedy underworld and a spiteful killer.”

“Nancy Khan” (S26, E3) Snapped on the Oxygen True Crime

Over the course of his life, THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD has watched hundreds, possibly thousands of true-crime documentaries. One thing THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD has learned in hundreds if not thousands of hours of watching is this: criminals are fucking idiots.

The concept of the genius mastermind evading detection for his or her crimes is a fictional fabrication — one created by a bunch of authorial Poindexters with way too much time and intelligence on their hands, and not enough experience in the real world or common sense to make their literary nonsense believable. Ted Bundy was no Moriarity; the police had numerous opportunities to catch this fucktard, but they fucked them up. Several agencies fucked up. Majorly. And some, like the King’s County Sherriff’s Department, fucked up repeatedly.

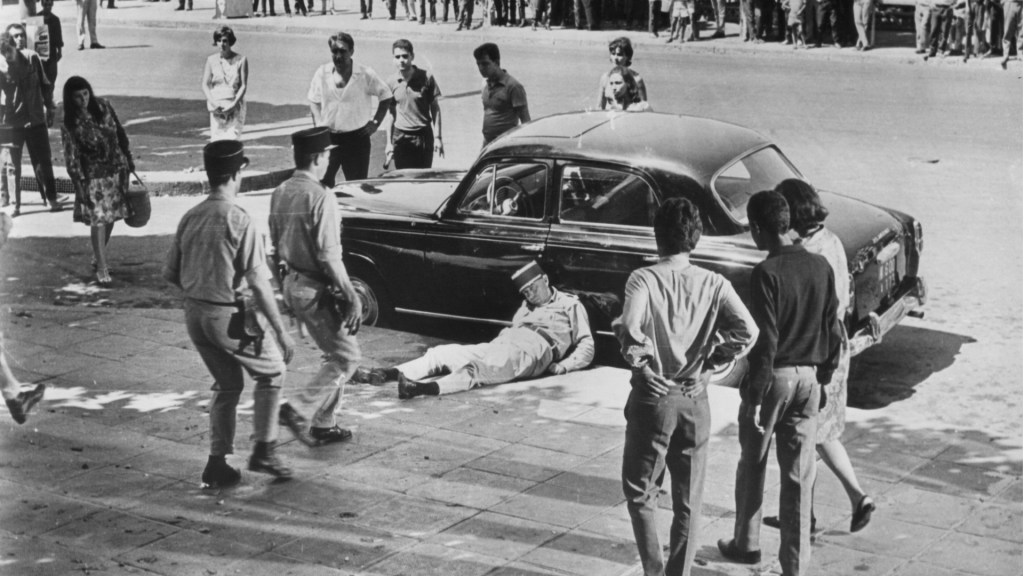

Keystone Kops

“Before doing anything else, [King County Sheriff’s Department Major Richard] Kraske decided to call in the department’s divers for a thorough search of the river. And before allowing either of the bodies to be moved, Kraske also called for the medical examiner. Kraske remembered how potentially critical evidence in the “Ted” [Bundy] murders was improperly handled at the time those bodies were discovered, and how later confusion over which bodies had actually been found where had complicated matters. He also remembered a handful of television reporters in the “Ted” murders who worked their way around the police lines to walk through the areas where the skeletons had been found, possibly tearing up some of the evidence before anyone else had a chance to search. Kraske decided that this time, at least, nothing would happen until everything was ready.

. . .

“Three bodies! Kraske felt staggered. In the core of his being, Kraske knew it was happening all over again, just like in the Ted murders. Quickly Kraske told [King County Sheriff’s Department Detective David] Reichert to freeze. Other officers were told to rope off the area where Reichert was standing. No one except Reichert, no one, ordered Kraske, was to enter the area where Reichert was until the medical examiner arrived.“Temporarily immobilized, Reichert looked down at the body he had almost stepped on.

. . .

“By now the divers were in the water. A helicopter was being summoned to search the channel by air in case there were still more bodies. Several of them were smoking as well, dropping their butts at random. Ainsworth thought that was odd. Didn’t the police care about contaminating the crime scene? The way they were going, it was soon going to be impossible to tell what had been present before their arrival.”The Search for the Green River Killer

Carlton Smith and Tomás Guillén

There are several reasons for why crimes go unsolved (including those demonstrated above in Keystone Kops): lack of evidence or a perceived lack of evidence; police disinterest, malfeasance, and mistakes; misattribution of a crime as something it is not (e.g., the coroner or medical examiner misidentifying a murder as a suicide), jurisdictional pissing matches; prosecutorial indifference; inaccurate, erroneous, lost, or misplaced evidence and evidentiary records; misused or disused detection tools, computer systems, and protocols — the list is almost as long as some of the criminals’ rap sheets. But THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD believes no crime is unsolvable; it simply may not be solvable now due to many of the reasons listed above.

Take as evidence supporting this claim the plethora of cold case crimes that have been solved thanks to DNA: a forensic method for detection that didn’t legitimately exist before 1986. DNA was first used in forensics by Alec Jeffreys, who developed the technique of DNA fingerprinting to help solve the murders of two 15-year-old girls, Lydia Mann and Dana Ashworth, who were raped and murdered by Colin Pitchfork, perhaps the single-most aptly named criminal in the annals of crime history, in Narborough, England.

Use of DNA in criminal detection was the natural evolution of earlier forensic scientific methods, including blood typing and forensic odontology. Indeed, some forward-thinking detectives and police departments began seeing the writing on the wall as early as the late 1950s when they began collecting and preserving evidence taken from a crime scene.

Blood Typing

Note: Blood typing, which is a primitive precursor to DNA testing, was used in numerous cases since its inception in 1902. The ABO blood typing system was discovered in 1901 by Karl Landsteiner in Lyon, France, and has been used throughout early forensic history to help narrow down a list of suspects. It was considered circumstantial evidence and needed corroboration from other evidence to be valid evidence in a court of law.

So, who’s to say where science may take police detection in the future? Well, science fiction writers, Isaac Asimov and Damon Knight, that’s who. In Asimov’s 1956 short story, “The Dead Past” (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1956), the author predicts the development of the chronoscope: a device which allows viewers direct observation of past events.

Similarly, Damon Knight’s 1977 Hugo Award-nominated short story, “I See You” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, November 1976) predicts a near future in which cheap chronoscopes (or Ozos) are available to anyone, (An ozo is used in this story to witness the assassination of President John F. Kennedy by three assassins as his motorcade drives through Dealy Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1964.)

So, more rhetorically, who’s to say where science may take police detection in the future?

Anyway, back to the subject of “Stupid Things Criminals Do.”

In the aforementioned eponymous episode of “Snapped,” Nancy Khan is the wife of a man who has been shot dead in the couple’s bathroom. During Khan’s initial police interview the morning after the crime, Khan tells police that she and her husband had argued earlier in the evening when he left to meet a friend at a local strip club. Khan further stated that she packed a suitcase and left to stay overnight with a friend but checked back throughout the night to see when her husband returned home. That, Mrs. Khan stated, was when she discovered her husband’s body early the next morning.

Now, THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD is no criminal mastermind — hell, he’s not even a criminal mind at all, having committed nothing more than misdemeanor crimes and traffic violations in his youth. For that reason, readers are advised not to ask criminal advice of this small-time misdemeanant.

However, since THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD has read, listened to, and watched untold volumes of true-crime content, readers can count on this writer for advice on what not to do when committing a crime.

Like admitting you and your husband argued the night before he was murdered in your conjugal home.

THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD cannot count the number of true-crime episodes he has watched in which a family member, friend, or suspect admits to having argued with the victim shortly before the crime in question. In the vast majority of those cases, that person is later identified by law enforcement as the perpetrator of the crime and sent to the stripey hole for their stupidity.

The detective offers a cigarette, not your brand, and begins an

uninterrupted monologue that wanders back and forth for a half hour more, eventually coming to rest in a familiar place: “You have the absolute right to remain silent.”Of course you do. You’re a criminal. Criminals always have the right

to remain silent. At least once in your miserable life, you spent an hour in front of a television set, listening to this book-’em-Danno routine. You think Joe Friday was lying to you? You think Kojak was making this horseshit up? No way, bunk, we’re talking sacred freedoms here, notably your Fifth Fucking Amendment protection against self-incrimination, and hey, it was good enough for Ollie North, so who are you to go incriminating yourself at the first opportunity? Get it straight: A police detective, a man who gets paid government money to put you in prison, is explaining your absolute right to shut up before you say something stupid.Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets

David Simon

But, of course, you pay no attention to the good officer’s legally required recitation of your Miranda rights and begin talking your chuckle head off about your direct involvement in the crime — just like murderess Nancy Khan did on the morning of February 28, 2015.

Why — why would anyone who just committed the crime of murder start telling detectives they argued with the victim just before they discovered the victim’s body? Well, the good David Simon once again has the answer:

“The only answer,” mused Garvey as he typed the warrant for Vincent

Booker’s house, “is that crime makes you stupid.”

Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets

David Simon

There are several other stupid things that stupid criminals do that give away their stupid crimes to the sometimes stupid cops: revisiting the crime scene; trying to involve oneself in the investigation to, you know, get information on where the cops are investigating; telling one’s friends or family members one committed said crime; storing evidence from the crime on your person, in your vehicle, or in your residence; sending mail or leaving notes written in your own hand at the scene of the crime to taunt the police; posting videos or photos from the crime on social media; and so on and so on and so on. . . .

In fact, opening your mouth during questioning is probably the root cause stupidest thing a person can do, next to agreeing to a warrantless search of your person, vehicle, or premises, or agreeing to take a polygraph. Regarding the former, making the police get a warrant for a search buys time for you to get rid of evidence you may have stupidly kept or forgotten you had. Regarding the latter, here’s all you need to know about polygraphs:

- Polygraphs are inadmissible as evidence in a court of law because they are not reliable science. One does not have to look through volumes of case law to find cases in which a suspect was cleared as a perpetrator by passing a polygraph, only to be later found guilty of said crime based on actual admissible evidence: there are thousands of such instances.

- Though inadmissible as evidence, police nonetheless use polygraphs to direct their investigations toward or away from a suspect — which is fucking suspect in itself. It’s particularly suspect when you recall that law enforcement once employed the aid of psychics to help with investigations (as they did in the cases of the Boston Strangler and the Atlanta Child Murders — both to no good end) and hypnotism, which is almost always thrown out of court laughingly by nearly every judge who ever sees it presented in his court of law. (For more on dubious detection, check out optography, which, among other dubious detection methods, was used in the search for Jack the Ripper.)

- Almost no cop arrested for a crime will submit to a polygraph — certainly not if he’s listening to legal counsel or his union representative, both of whom will clearly advise him no to. It’s worth noting further that law enforcement cannot be compelled to take a polygraph if they are arrested for a crime. Likewise, civilians cannot be compelled to take a polygraph; however, failure to do so often moves a person up the suspect list since cops view invoking one’s civil rights as suspicious behavior.

In any case, THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD has seen far too many episodes of true-crime documentaries to know that arguments just before a murder — just like murders on or adjacent to holidays — are seldom coincidental.

Leave a comment