The following is a list of films about revolution and political upheaval. Note that this list of films is comprised mostly of fact-based fiction films (Animal Farm and 1984 are included due to their historic literary importance) and does not include documentaries.

Likewise, the list does not include war movies except for those depicting civil war (but not the Civil War). Finally, the list does not include SF or fantasy films with largely fictionalized revolutions as their backdrop. (In short, no Star Wars despite the entire premise of the Rebel Alliance.)

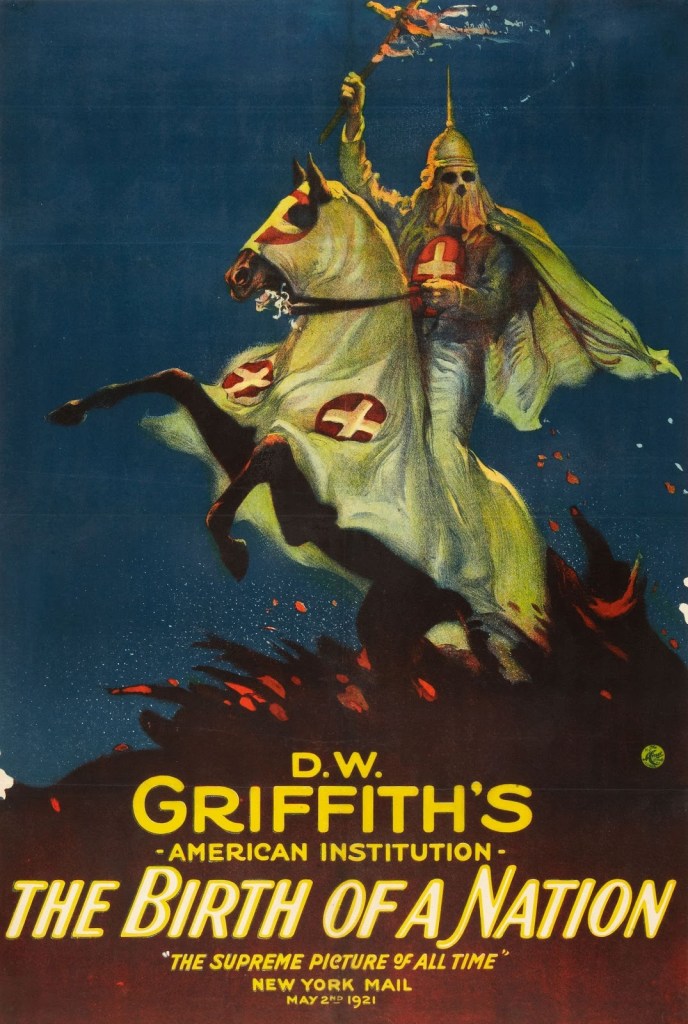

Films marked by an asterisk are strongly recommended, sometimes with caveats (as in the case of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, which despite its historic importance to the history of cinematic narration, is a rankly racist film that glorifies the Ku Klux Klan and vilifies African Americans — see Notes on Individual Films: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation after the list).

- Madame Guillotine (1916) Enrico Guazzoni and Mario Caserini, Italy

- The Birth of a Nation (1915) D. W. Griffith, USA *

- Danton (1921) Dimitri Buchowetzki, (Germany)

- Strike (1925) Sergei Eisenstein, USSR *

- Battleship Potemkin (1925) Sergei Eisenstein, USSR *

- October: Ten Days that Shook the World (1928) Sergei Eisenstein, USSR *

- Danton (1931) Hans Behrendt, Germany

- ¡Que viva Mexico! (1932) Sergei Eisenstein and Grigoriy Aleksandrov, USSR

- The Informer (1936) Carol Reed, UK *

- La Marseillaise (1938) Jean Renoir, France *

- The Fallen Idol (1942) Carol Reed, UK *

- Animal Farm (1954) John Halas & Joy Batchelor, UK

- Viva Zapata (1952) Eliz Kazan, USA *

- 1984 (1954) Michael Anderson, UK

- Spartacus (1960) Stanley Kubrick, USA

- The Manchurian Candidate (1962) John Frankenheimer, USA *

- Zulu (1964) Cy Endfield, UK

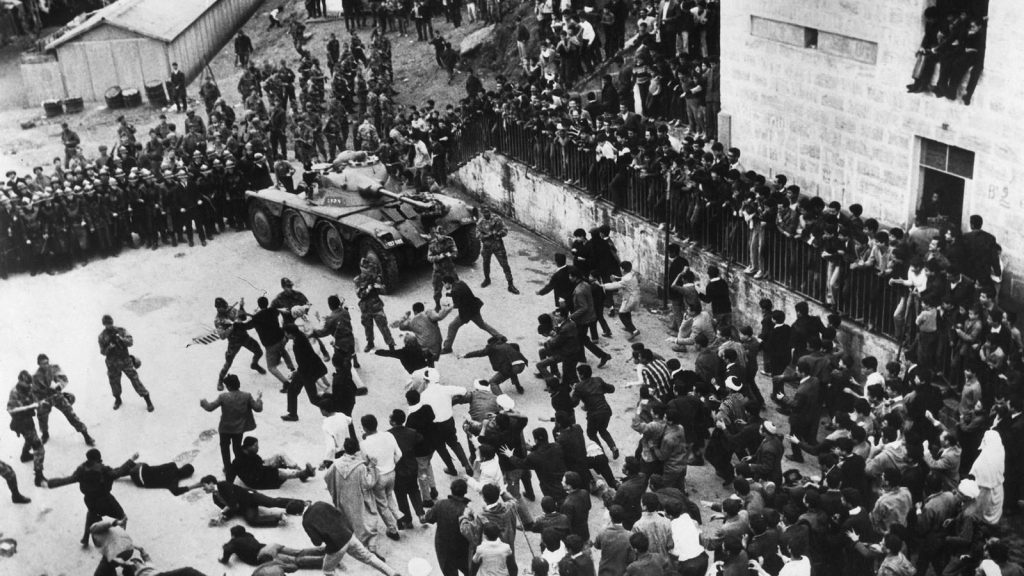

- La battaglia di Algeri, or The Battle of Algiers (1966) Gillo Pontecorvo, France *

- The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, or Marat/Sade (1967) Peter Brook, UK *

- Start the Revolution Without Me (1970) Bud Yorkin, UK/USA

- The Devils (1971) Ken Russell, UK

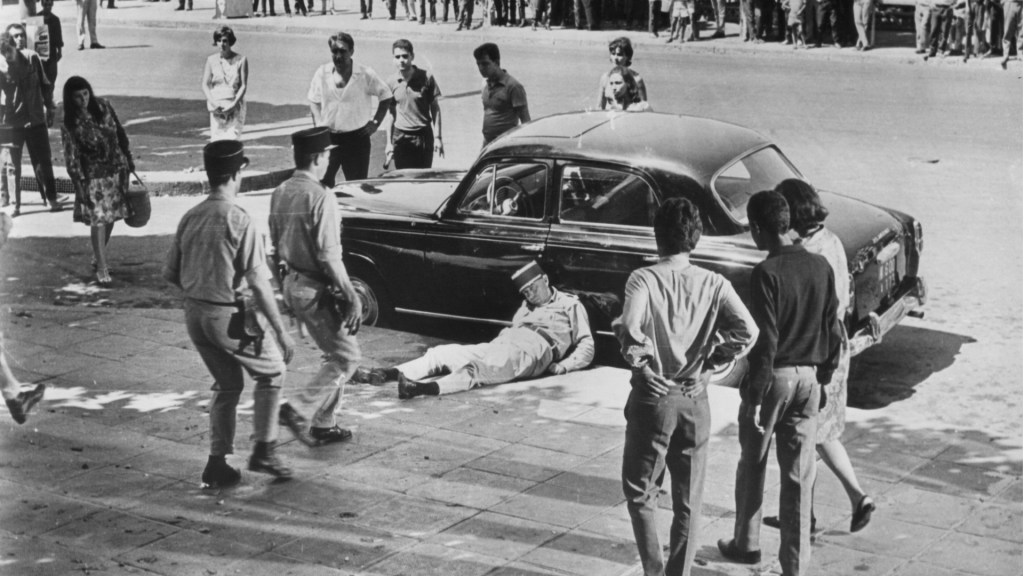

- Z (1971) Costa-Gavras, Greece *

- Tout va Bien (1972) Jean-Luc Godard, France

- Cromwell (1974) Ken Hughes, UK

- All the President’s Men (1976) Arthur Penn, USA *

- Reds (1981) Warren Beatty, USA

- Gandhi (1982) Richard Attenborough, UK

- Missing. (1982) Costa-Gavras, USA

- Danton (1983) Andrzej Wajda, France

- Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) Michael Radford, UK

- Salvador (1986) Oliver Stone, USA

- L’ultimo imperatore, or The Last Emperor (1987) Michelangelo Antonioni, Italy *

- Farewell My Concubine (1993) Chen Kaige. HK/China *

- The Crying Game (1995) Neil Jordan, UK *

- Michael Collins (1996) Neil Jordan, UK

- Bloody Sunday (2002) Paul Greengrass, Ireland/UK *

- Marie Antoinette (2006) Sofia Coppola, USA

- Persepolis (2007) Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi, France *

- Che Part One and Part Two (2008) Steven Soderbergh, USA *

- Argo (2012) Ben Affleck, USA *

- Belfast (2021) Kenneth Branagh, Ireland *

An Explanation for Exclusion

I am not averse to listing documentaries — in fact, I prefer documentary films to fiction films — but the higher standard I set to documentary films makes any list I compile more difficult. That said, documentary-themed lists will be forthcoming at some time in the near future.

Notes on Individual Films: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation

film ever made.

Although this film is historically important to American cinema — in truth, to the development of cinema itself — the film is abhorrent due to its racist topical matter. And in spite of D. W. Griffith’s enormous contribution to the technical and commercial growth of cinema, the racist, white supremacist beliefs espoused in The Birth of a Nation were equally deleterious in their popularization of the Ku Klux Klan in the early decades of the 20th century.

On the one hand, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation is essential viewing for any serious student of film history, theory, and production. The film is monumental for several reasons: its use of close-ups and establishing shots to develop a cinematic syntax; its use of matched action cutting to tell concurrent narratives and to build tension between storylines; its utilization of fade-ins and fade-outs to denote a passage of time or change of setting; and its implementation of an orchestral score to help establish mood and tone, to name but a few.

At three hours and 50 minutes in length, The Birth of a Nation was the first non-serial 12-reel film. Produced from a budget of $112,000 in 1915 (roughly $4 million adjusted for inflation), it was one of the most-expensive movies ever produced at the time of its creation. Even at that then-exorbitant production cost, the film grossed between $350-500 million (adjusted for inflation). Last, the film employed one of the largest crews of actors and extras for the time: the film employed a literal army of extras to re-create Civil War battle scenes fundamental to the film’s plot.

The Birth of a Nation draws reverently from its source, The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, the pro-segregationist second book in a trilogy bookended by The Leopard’s Spots and The Traitor written by Thomas Dixon, Jr. Though both book and film are works of fiction, Griffith’s depiction of Civil War battle scenes are surprisingly accurate with respect to historical authenticity.

That should address the film’s positive and ambivalent elements; let’s discuss now The Birth of a Nation‘s other hand.

On the other hand, there’s the deplorable, truly inexcusable racism espoused by The Birth of a Nation.

I won’t bother with a synopsis of the film’s plot — not to avoid spoiler alerts but because the quasi-historical, racist plot is probably the least interesting element in the film. Suffice it to say, The Birth of a Nation tells the story of two families — one North, one South — separated by the Civil War. The film re-creates several Civil War battles as well as the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. That’s really all one needs to know about the plot of this film.

I will, however, address the abject racist tone and tenor of Griffith’s “masterpiece” since it is probably the film’s most salient (if dubious) achievement other than the film’s groundbreaking technical accomplishments.

The Birth of a Nation is mired in the cesspool philosophy espoused by William Archibald Dunning and the Dunning School of thought, which unapologetically lionized pro-segregationist Southern plantation owners, former Confederate soldiers, and supporters of the Confederacy, while disparaging Republicans who opposed segration and favored civil rights for former slaves. Vehemently white supremacist, the Dunning philosophy is central to Griffith’s film: The Birth of a Nation wouldn’t exist were it not for this core racist philosophy.

Born in Oldham County, Kentucky in 1875, D. W. Griffith is very much a product of his time and place of birth: his father was a colonel in the Confederate Army and a Kentucky State Legislator during Reconstruction. Raised Methodist in the Deep South, Griffith is the poster child for white supremacist thinking and racist philosophy.

In spite of Griffith’s importance to the evolution of early American cinema, I stand by these characterizations. Nothing Griffith did as a filmmaker excuses his beliefs as a white man in the Deep South in the early 1900s — a time when the KKK was making a comeback nationwide, no doubt due in large part to Griffith’s film’s aggrandizement of this no longer just-Southern hate group.

At its core, The Birth of a Nation depicts African Americans in a grossly pejorative light. At the same time, the film sickeningly glorifies white supremacy. (I mean, for fuck’s sake, Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation portrays the KKK as the film’s heroes!) And the film maintains these views in spite of popular appraisals by W. E. B. Du Bois and other proponents of racial justice that African Americans merely defended their rights as American citizens during Reconstruction, while the KKK, a legitimately labeled terrorist organization, intimidated, abused, and even lynched African Americans nationwide to silence that justice.

Despite their love of social justice [sarcasm alert], American audiences flocked to this controversial film, making it one of the most commercially successful films of that time. Moreover, the film revolutionized cinema at a time when filmmaking was still in its relative infancy. And to his credit, Griffith (along with Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks) founded United Artists in 1919 with the goal of empowering actors and directors to produce films free of the strictures imposed on creativity by commercial studios.

But in spite of all of that, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation is still one of the most controversial films produced and a sad testament to a time when white supremacy and violent racism were fully embraced by a mostly segregationist American public.

Cunning Distractions: “The Manchurian Candidate as Horror Movie” — Coming Soon to THE NORCAL PECKERWOOD blog.

Leave a comment